Saturday, January 28, 2023

A Cautionary Tale

Friday, January 27, 2023

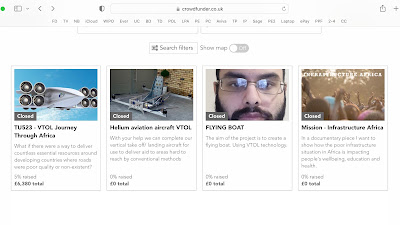

Crudefunding UK

Thursday, January 26, 2023

Purchase History

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

30- by 12-inch

The patent agent in Turkey presents an annual bill by way of a subscription, which is a good opportunity I feel for abandoning the process altogether. Boosted by a pandemic examiners here ~ as in the UK and US ~ have yet to come back with a response to the request for a search. In a way this is good, as it allows me to present myself as a "Prof Pat Pending".

Nonetheless I agree with James Dyson's views on the inadequacy of the patent system when it comes to assisting individuals or small firms in getting an idea off the ground. It has become (and especially so in the 21st century) simply the means for corporate cartels and monopolies to tighten a stranglehold on the commodities of everyday life.

In retrospect the design registration system makes for an altogether better record for any product development, and although Duncan Bannatyne said on "Dragon's Den" that designs are easily circumvented by minor variations, so too are most patents; such that a system developed in Jacobean England to advance technological progress does as much nowadays to stifle it.

In the interim I'm looking at crowdfunding. A review of Kickstarter rules says that they do not accept either heavily regulated or dangerous activities, which to my mind rules out aviation at the get-go. I put it to them in accordance with advice on the website, and I get a boiler-plate reply of no real use, albeit from a Titus Muchiri who does have a great name: African apparently, meaning "settler of arguments".

Great name for a guy in support at Kickstarter. Worked myself for Wang Computers for a while in London, whose own support program was called "Wangcare".

A name that might not ~ we suggested ~ go over quite so well in the UK?

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Bell Whither?

Monday, January 23, 2023

Back to the Future

Pendulous stability as it relates to drones appears to be a myth if the valuable opinion of Tom Stanton is taken into account at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYHCP3-mpxk is to be believed. Conventional aerodynamics however have always regarded helicopters as being stable for precisely this reason, whether true or not, though the difference between the two types of aircraft is as much a reflection of the fact that a main-rotor has considerably more leverage I suspect. Tom Stanton's video suggests that drones with a decidedly low C of G are set to struggle... a view I've heard from various sources involved in real-world experimentation with drones.

Most of those involved in building drones, in fact, evolved from an interest in RC helis and in fact many of them prefer the latter as a flying machine given the limitations of drones at least in so far as flying people around is concerned. Nonetheless the fact that eVTOLs will succeed and displace or at least supplement the helicopter ~ to the extent they will far outnumber them ~ is inevitable in the way that electric motors will inevitably replace combustion engines in cars.

Before the expense of launching a working prototype (even at scale) therefore, it may be worth reviewing the options... one of which appears above. Prototypes are ideally an exercise in step-change where they start as the simplest and lightest embodiment and accrue the more practical accoutrements only later on. The automobile is as good an exemplar as any, in fact, having started out as an open-topped horseless carriage.

Accordingly the planform on the right provides the same leverage in flight, although it reduces the dimensions of the airframe by a third at the same time. It will tho' involve the centre-section in being reduced to an eight-inch square containing the mannekin instead of a twelve-inch, although I think this is workable in the first instance. At full scale it represents a four-pillared outline of sixteen inches, ample for supporting my own frame at the outset for instance.

Rather than adding motors to the drone up top, therefore, it would suggest re-visiting the previous solution I've implemented in past experiments to address an insufficient leverage around the centre of mass viz. replication of the same airframe around foot-level as well as above head height ~ in fact at the earliest stages of development this solution was only abandoned because it pitched the overall dimensions of a people-carrying drone outside the allowable constraints of the GoFly competition back when.

A temporary setback, but then nothing worthwhile in life ever comes easy.

Thursday, January 19, 2023

SCALING UP Chapter Twelve

TRANSPORTS OF DELIGHT

In truth, whereas the child is considered father to the man there would be nothing that might hint at my own future beside a leaning toward transport in all of its forms; and it is conceivable that my attempts at designing boats and VTOL aircraft derive from missing out on careers featuring either. And in truth, I enjoy driving articulated trucks in view of the fact it doesn’t need to be done at the exclusion of all else… although there are any number of hauliers out there that are happy to arrange your life that way. And besides, didn’t Mike Davis combine trucking and meat-packing with academic treatises on his home town of Los Angeles or the condition of both working classes and environment?

As autumn beckoned in 2022, though, I finally had the leisure to consider whether building a personal air vehicle retained any traction in my daily affairs. Was it not Solomon who had said that as as the dog returned to its vomit, so the fool returned to his folly. Bit harsh, that one, and I prefer the one about all progress having always depended upon the unreasonable.

It might then be a time to revert to first principles, and these had been to build a form of transporter in the shape of an upright booth. Originally and in view of the weight of what is involved in producing sufficient lift, I envisaged this booth being surrounded by an airframe sat at ground-level initially for fear of it toppling over. Subsequently it would power itself up into the overhead, where it would engage with the overhang of the booth so as to elevate it skyward. This notion would fall at the first hurdle when you looked into the detail, for drones are controlled by a computerised flight-controller that ideally sits at the centre, where my airframe had to include a void that enabled the accommodation to take centre-stage. Beside this successive build showed that this centre-section was where the structure derived much of its strength.

One get-around featured instead of a booth merely a set of four tubes that allowed the drone to rise whilst including only a hole at each corner. It allowed the flight-controller to remain centred, though it would mean a passenger boarding once rotors were turning up top. In terms of rigidity it could also be made to support a considerable weight were it braced around half-way up, where it effectively halved the length of each tubular column. Nonetheless, a rigid space-frame still knocked it into a cocked hat and especially so when reinforced in the same way. It also helped secure the operator whilst providing both an armrest and a deck upon which to mount flight-controls in the form of sidesticks. Whilst in its original form it had been made of a single piece that could be pulled upward like a pair of underpants (and you won’t find that in the Airbus lexicon), eventually it proved both to be more snug and more practical if split fore and aft.

Above all, however, it rendered the vehicle altogether more purposeful in both my own eyes and more importantly, those of potential purchasers. A sure sign too that there was interest out there was when I posted ‘how-to’ on the blog instead of opinionated fare that frankly few of us would be interested in. Without windows and without some form of restraint the box also looked like something people might step out of at a great height had they seen the latest gas bill… might that be my killer app? All in all, as I assembled it step-by-step during the closing months of 2022 it appeared to be an altogether better proposition than the one with the same form of drone fitted with a seat above instead.

In ergonomic terms too it held out better prospects, for the moment you introduce a seat you have to consider shapes and sizes accordingly and there were even books out there that listed average dimensions from among the general population. Thus it was that Jetson did list a target size around which their own vehicle had been designed: five feet ten inches, as I recall? This is less of an issue however where only manual controls are required, which only go to show what sort of a sea-change the electrification of flight would prove to be. For among the most complex part of designing every airliner is how the seating might be arranged on the flight-deck in order that pilot and co-pilot are able to reach every possible control that they might need to… not least the rudder-pedals, which had been fitted to aeroplanes from around the get-go.

Thus were the ‘drone was concerned where it could be fitted up top, it meant that the booth might be broadly configured to both the shape and size of an individual whilst still retaining a standardised means of connection (you can tell I’ve long drafted patent specifications) between the modular ‘drone and phone’. This was especially so as regards the height of each of us, where for example my elbows rest at a height of a metre such that a box two metres high would be suitable ~ “Suits you, Sir!” ~ when considering that the batteries would be stored in its roof-space.

There was also a good deal of latitude when it came to the dimensions of the box determined by the distance at which each upright were fixed. Although I had tinkered with rectangular outlines (because we are generally wider than we are deep), the brand called for a square ‘phone-booth’ and not least in order to emulate my booth of choice in the shape of the General Post Office’s magnificent K8. I had even considered buying one of these to mount in the garden, but settled for taking pictures of such wherever they might still be encountered. Note to fellow boxers: there remains one in the village of Ingleton.

For what I had noticed early on, and which went to show that there was no substitute for experimental builds, was that we could actually slip sideways into a much narrower gauge of box than we might imagine. You needed to be careful including your child in such experiments, incidentally, for fear of being viewed as the kind of Victorian gentlemen who’d send them up chimneys in days of yore. Even where I was concerned myself, though, I figured I could be squeezed amongst four pillars spaced as little as a foot apart and still be suspended from a giant drone in my dreams.

The half-scale prototype in view featured a foot-square outline, and this raised the question as to whether its occupant could comfortably stand with their upper limbs inside the box, or hanging without. The only way to tell was to secure a child-sized mannekin that had articulated arms, and a sweep of the ‘net proved these to be as rare as unicorns in a post-pandemic world that had disrupted supply chains everywhere. I managed to find one such, however, and it would eventually show that whilst it might be squeezed into the box like a sardine, it would be rather more comfortable with its forearms resting outside of the box with a pair of sidesticks to hand. In the event with the articulated type looking somewhat heavy for the choice of motor I envisaged, I would also travel to what can only be called Britain’s largest mannekin graveyard… but that’s another story. (Standing child-sized rigid mannekins were easier again to locate than seated, though I had to confess I’d looked up so many online that I feared a visit from the Vice Squad.)

The new mannekin stood proudly a metre tall, as it seemed to be a fairly standard measurement. This meant happily that it would fit inside a box constructed of metre-long tubular sections, a relief in itself in view of the fact that was the measure that they came in as well. This was only though because the tube-connectors that terminated each of the uprights added a couple of inches to the interior volume. It raised the question of where to include the sizeable battery-packs, and in the end I would settle for doing so in the loft space of each booth. It meant that such an area would have to be added in future builds, but the advantage of the modular design was that both box and drone could be modified wholly independently of each other. More importantly the TELEDRONE logo could appear in the sides fitted at the upper end of the booth, which would surround the battery-bay as those at the lower end did in order to form the foot-well.

The lighter of the two mannekins ~ by dint of rigid fibreglass arms instead of wooden ~ was used as well as the articulated version in the studio shots, but at the time of writing it is the articulated type that will form the phenotype to the design’s genotype: it was nonetheless looking like no mannekin would appear in flight-testing at the outset in view of the paucity of power from the motors that had been selected. I was comfortable with the prospect not least because we had flown both the drone in its current form, as well as a drone with an underslung accommodation box. At the same time if you looked at the history of aircraft design it has been one of manufacturers desperate for engines that produced more power in order to get the proposed outline off the ground.

The decision then to include an upright operator was proving to be sound; looking further afield it appeared too that one thing electrification offered to VTOL designers was the freedom to decide where and how to include that operator. Almost invariably those alternative designs out there mounted people atop drones, for the very obvious reason that it was easier to pitch what were increasingly massive drones at floor level and then let the pilot clamber on top. The laurels of victory I considered would go to those able to conceive of ways to reverse the arrangement. This was not least because having learned aerobatics at the very earliest stage of learning to fly, I preferred the idea of the vehicle remaining upright in the event of a power-off and hands-off freewill. This was something not every eVTOL was assured of, especially if it were the case that the pilot up top were the heaviest aspect of the ensemble, whilst the draggiest part in the form of its feathers viz. propellers were beneath: think of the way a dart settles under gravity.

Why though not follow the alternative any number of projects had adopted, as had the car before them, with a support at each corner albeit a motor instead of a wheel? To a great extent though this ‘flying car’ configuration was neither novel and nor indeed did it require a great leap of imagination, in so far as drones (and especially racing versions) were universally configured along he same lines. It may yet be that such a layout evolves to become as standard a layout as had the four-wheeled car prior, yet I was unconvinced that this would be the case. Principally this was because, whilst it was true that the main-rotor helicopter dominated the market it would never yet supplant three other successful variants in the shape of the Chinook, Kamov or Kaman. It might yet be that a distributed array of electrical propellers would eventually render each of these configurations extinct in the way that mainframe computers would be overcome by a multiplicity of distributed processing power in the shape of smartphones.

A further advantage lay in the fact that a modular solution might prove as resilient, in so far as a vehicles like the Jetson or Blackfly was a unitary construct like the car that could not take up less space by being separated into principal components and hung from the garage wall, for instance. Finally however I felt that the TELEDRONE might occupy its unique ecosphere from the point of view that its appearance was at once familiar (except to the very youngest, for whom it might appear to be a relic of TV repeats from Star Trek or Doctor Who), and at the same time readily connected to its layout viz. pilot suspended from drone. A final reason for not having abandoned the branding too, was that my father brought us up upon the earnings of a telephone engineer. Were then my son to inherit the mantle of TELEDRONE engineer, things might be viewed as having come the full circle.

|

| Forty kilos up. |

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

SCALING UP Chapter Eleven

ARTY FACTS

It was around this time ~ during February of 2022 in the interregnum between the HGV classroom course and driver training in Ancoats ~ I felt it was time to donate at least a portion of the body of my art to posterity, by way of one museum or another. We have seen how the Hiller Museum in Silicon Valley had just missed out on the prototype that we’d travelled there with, not least because of the effort that would be involved in flying it back with us. Stripped of its essentials like something of an organ donor, therefore, it was passed on to a member of another of the teams at the GoFly Challenge and now as a consequence hangs from the ceiling of a warehouse in Los Angeles. It could be that if this were all to take off, the guy might have the equivalent of the original Mac hanging up there and readily saleable on eBay. And if so, good luck to him I say!

For the two-third scale prototype that had successfully flown during the previous December I elected to donate it to the Helicopter Museum in Weston-super-Mare in the south of England. This private collection begun effectively by just one man who’d been associated with the industry for many years was by then the foremost collection of rotary-winged craft in the world, and included the original helicopter built by an Austrian by the name of Raoul Hefner. He had exported his skills to the UK, Austrians no doubt feeling like most others at the time that there would be little use for such things. The one which most impressed me however was the Whirlwind from Queen Elisabeth’s ‘Royal Flight’, which he’d acquired for the princely sum of around fifty thousand pounds.

When you consider that a twin-turbine helicopter of this sort would cost many millions of dollars to replace and yet this one ~ resplendent in Royal colours ~ had been knocked down to a bargain-basement level. Thing though about helicopters, like many other forms of transport, is that they tend to evolve to ever higher stakes and are thus prohibitively costly to run and maintain once removed from their habitual domain. It was a reason that I liked the reductio ad absurdum of personal air vehicles, now that they could be put together by dummies like me. Until recently they had been just to difficult for anyone but the decided enthusiast to contemplate, chiefly because the only option for powering them was the internal combustion engine… and one as often as not derived from elsewhere (like lawn-mowers). It was thus like, for instance, trying to build a car from scratch, instead of simply referring to the classified ads and buying a used one.

In truth then it would be a lot easier to assemble a collection of helicopters than you might have thought. Not a few of them had been used on film-sets, having come to the end of their natural life. And what use would a studio have for them thereafter, given they took up rather mores shelf-space than an R2D2. One form of transport that always appealed to me from the point of view of being lived-out was the hot-air balloon, which have to be furloughed after a while because their fabric deteriorates under everyday UV radiation. There were lots of things you could do with a balloon I figured, as indeed you could with one of those giant cooling towers, by way of a last hurrah.

For my prototype’s last hurrah, however, it would be a life in perpetuity within the Helicopter Museum. The curator had ideally wanted something from Vertical Aerospace, but then beggars could not be choosers I figured. The important thing was, and here was a natural soul-mate of mine, there was an electrical revolution taking place in aviation that anyone visiting most museums would be wholly unaware of. This to a great extent is a British thing, we like nothing more than revelling in the past rather than contemplating a glorious future. It was the mistake that our short-tenured Prime Minister in the shape of Liz Truss had made… betting the farm on a techno-future in a country that relies for its well-being principally upon global financial corruption on the one hand, and buy-to-let renovations (and TV series to accompany them) on the other. We once revolutionised industry, but those doing so generally then upped sticks and moved their kids to the capital, where over successive generations they would invest in property and inflate the economy in order that they could enjoy a comfortable retirement, or that their off-spring would never be tasked with anything as materially constructive ever again.

One week later therefore I would visit another monument to a glorious aviation past, except located in the North of England. The irony is in all of this that in the UK it is a good deal easier to obtain funding for a museum than it is say for a personal air vehicle that some people at least view as a reasonable proposition, and that could be developed (if not certified) in a fraction of the time and budget associated with any other program. Prior to Liz Truss it was probably Boris Johnson who is PM best exemplified our ‘bull-dog’ spirit, but his principal adviser (and the architect of Brexit) viewed the country’s aircraft-carrier as a vainglorious piece of show-boating more likely to be sunk during the next asymmetric conflict than not… a sort of floating World Trade Center.

All of that said, however, I do love a good transport museum and this one was the sort that just put it out there for what it was. Whilst night-stopping at Teesside Airport as aircrew I had visited a local museum that contained what is practically the first steam locomotive anywhere in the world, and marvelled at material substitutions from a time when there would have been decidedly little choice: most notably the use of leather for seals, when even rubber would have been absent from the world and let alone plastic.

Another reason for having selected the South Yorks Aircraft Museum was that it was located in Doncaster, a place I’d travel to on a rail warrant before decanting to RAF Finningley for a weekend of flying training. It’s own airport had long gone, having been landscaped for the inevitable smorgasbord of duck-ponds, crap statuary and shopping centres. In one corner of what once had been, however, there remains the hangars and in them the museum’s collection… amongst them the back-up prototype to that left in amongst the inventory in Weston. This one to would hang from the rafters adjacent a parked Bell 47 of the sort I used to watch crop-spraying as a kid (and whose chemical exposure likely led to the current fixation with building a flying phone-box).

What needed to be done now, however, with these scale prototypes safely tucked up, was there scaling-up… at least in mock-up form for the essential look-and-feel prior to cutting metal. This required the exercise of imagination in itself. For motors I used a set of foam-planters from a flower-arranging website, for each battery a shrink-wrapped length of timber and for propellers the fascia-board you’d see on uPVC conservatories so beloved of the your neighbours and mine. Thus rendered it would be sufficient for studio shots for the PR push at least, but more importantly it would allow me to sit in it. Sat as it turned out on a £9 folding chair from IKEA, which I can recommend for its levity if not its crash-protection.

This would be an invaluable exercise, for it revealed if nothing else that all eVTOLs with propellers located on the underside are a potential death-trap requiring a relatively complicated ~ and heavy ~ form of protection for the inhabitant. Beside this, all else being equal in a power-off free-fall such aircraft would eventually fall to earth inverted, along with that same inhabitant. Above all, once scaled up to adult size it neither felt right sat with me sitting on it, nor looked right from the photo of me doing so from the visit to the studio. And one had to be ever wary of public perception, the C5 electrical three-wheeler having sunk the reputation of Sir Clive Sinclair. It was not so much the fact that it was powered by a washing-machine motor that would not have captivated the fans of Fast and Furious, say, but that you looked a bit silly whilst motoring along the road in it. This last aspect was only worsened by the addition of a flag-pole with a pennant atop it that the average motorist my spot prior to squashing it like road-kill. If anything, this made it look as much a moving target for golfers as a means of mobility.

Accordingly this meant ultimately that I would dismantle the mock-up and shift it to the recycling bin, in a way that say Van Gogh would periodically trash his paintings if not cut his ear off and send it to his beloved. (Tip to teenage readers, incidentally, a box of chocolates is altogether the better choice from either point of view.) In truth this left me in the Slough of Despond, and this from a man who survived office life in the Slough of Berkshire… and in fact whose office appeared had appeared in the opening frames of Ricky Gervais’ eponymous TV comedy. As a consequence, and to the detriment of a blog in our always-on world in which we all either thrive or die (and nothing in-between) on social media, very little would happen for many months afterward. At least drone-wise.

I’d walked out of the first trucking job ~ a sugar-rush experience which most of us only sensibly dream of ~ and landed a second, dropping food cages at branches of Tesco at what I considered to be a plain silly hour of day. This was an eye-opener in itself, as I came to realise that the entire logistics industry in the UK is staffed with cheap labour from Eastern European (and I mean cheap only in the fiduciary sense), along with bored old men like myself. I would leave there having been told, when delicately suggesting like Niles Crane to a large Irishman that he may have been parked in a Loading Bay, that I go fuck myself. I thanked him for his wise counsel, and never darkened Tesco’s door again.

|

| Mothercare to museum... |

SCALING UP Chapter Ten

GEARING UP THE DAY JOB

It was December 6th of 2021 that Angus flew the seated two-thirds scale drone with some panache on a serene and sunny winter’s day that made for a great video. As it turned out it would parallel the Wright Brothers epic flight that same month, though principally because there would be practically nobody there to see it beside Angus himself and someone collared in the model-flyers’ clubhouse to wield a smartphone.

The reason I wasn’t there myself was on the one hand because Angus preferred to be left to do his own thing on days like these, but also because I was otherwise engaged myself. By this time was already some months into a modest monthly payment from the UK social welfare system… an oxymoron in itself a dozen years into Conservative rule. Where I lived you were generally guaranteed not to be offered any form of day job, for the simple reason that there wouldn’t be any… like living in Detroit as an auto-worker.

I was though required to list five jobs that I would consider, beside ‘phone-box test-pilot’ or indeed ‘next unicorn’ and aside from gardening I recall having listed driving among the options. Undertaker I had considered, having heard of someone who baked magic mushrooms into the sponge cakes at crematorium in order to guarantee all those attending the send-off of all send-offs. At university, in a similar vein, the only jobs that had ever appealed from off the printed circulars were (a) lighthouse keeper and (b) Hong Kong policeman.

“Great news!” Said my jobs mentor, as I eyed her warily. “It just happens there’s a government-funded HGV course starting in ten days!” she continued, and at a stroke I’d been signed up. This was something of a relief. I’ve never viewed myself as work-shy if only sufficiently motivated, for example by climbing the stairs of a lighthouse to check out the weather each day. At the same time I needed a regular break from building life-sized drones for my own sanity. It was what attracted me to life as an airline captain, in so far as inventing was regularly interrupted by flying and vice-versa. Beside this, I got to see transport museums all over the world by dint of contracts as widespread as Asia, the Middle East or Africa.

Great news indeed, then, in so far as six-week class-room element was to take place at facility a stone-throw from the house. I was too something of a veteran when it came to mature studentship, having been on countless aviation training courses since the get-go. This though would likely be different for the eleven of us present, appearing as an even broader and colourful ensemble. Like any number of aviation courses too, it would be peopled entirely by men. The guy next to me surveyed the enrolment form to be filled in at the outset, and asked me “What does LQBTQ mean?”. It was, I told him, a new European licence covering every class of Heavy Goods Vehicle. We still called them HGVs in the UK, pooh-poohing the EU-speak alternatives. Likewise employers still ask for Class 1 drivers for 44-tonne artics whenever they can avoid the meaningless “C+E”.

In truth, there are many corollaries betwixt driving airliners and driving trucks. My second cousin (second by remove, not literally second by issue) flew for EasyJet and as the airline had been curtailed by the Covid-19 pandemic, any number of its pilots were driving trucks instead… to the extent that of all the drivers on the books of one agency, a full third were EasyJet pilots. There were driving-time limitations, pre-operating checks, weight and balance calculations, cargo loading processes, accident and incident reporting, hazardous goods, health and safety, crew co-ordination issues and so on; all grist to my pilot mill.

In each case I would use my role-playing skills in class to add relish to the ‘scenarios’ that each us might face on the road or at one or other fulfilment bay: “Hello, which bay do you want me to use?” A colleague would ask, “Do I look like a fucking traffic light?” I would reply. Actually as it turned out on the job, it was the best possible introduction to life as a haulier in the north of England. On one of my first outings I parked my ‘rig’ kerb-side and strolled over to the gatehouse of a chemical works with an affable airline-style “Good morning!”. Without himself looking up, a guy who looked much like the one with the balloons in the movie UP replied “Fuck off”. Similarly in role-plays the ‘banksman’ could not be helpful enough in guiding you whilst reversing a 40-foot trailer into one or other parking place, whereas as often or not on the job you’d be asked “You driven one of these before?” to which I’d reply, “Yeah, for a week now…” and watch them back off.

Though I get ahead of myself. The reason there existed such a course as this was because the government in the UK like every other worldwide had cut everything to the bone and demolished the labour laws; to the extent anyone not flying around in personal rocket-ships was guaranteed a fairly shitty existence. As a consequence there were few people to drive stuff like petrol or PPE equipment around the place as the pandemic set in. As a consequence of this in turn, trainees would be allow to go direct to driving-tests on articulated trucks instead of having to pass one on rigid types instead. This I liked as I figured I’d be able to look down (almost literally) on Class 2 drivers from the get-go in the way that long-haul pilots sneered at short-. Experience would bear this out, as one guy would later tell me as we sipped coffee at a Tesco warehouse at 04:00 a.m. that he would not be going to the Christmas party, only to mix with drivers who’d not given him the time of day whilst driving Class 2s.

There are though any number of reasons why the average age of people driving trucks in the UK is fifty-five. One is the substitution of permanent roles with ‘gig’ jobs through agencies, which are great for twenty-five year old app developers but rather less so for fifty-five year old truckers. A second is the abandonment a general dismantling of labour unions, and nothing quite epitomises the destruction of blue-collar jobs in the USA for instance, than the fact that members of the Teamsters’ union who once ran the country… don’t. Thirdly the withdrawal of self-employment tax status among those for whom it was originally intended ~ by dint of any number of agency contracts ~ meant a larger take for HMRC at their expense. Fourthly the industry still struggles in attracting women to the role, not least because hitching and dropping trailers remains a job for better-endowed grease-monkeys; beside the fact that few of us male or female want to be watched trying to reverse one of these into a parking place. (And I discovered I was not the only tyro to pull into service stations and pull straight out again after surveying the lack of drive-through parking slots.)

Fifthly though (beside the amount of testing and qualification the role attracted, which was approaching that expected of the average airline pilot or engineer) there was the nature of the job. I quite liked it, for having spent hours staring out airliner windows at clouds while designing drones in my head, I could do so while surveying landscapes from another lofty eyrie. But in the age of TikTok videos and the chance to dance like a monkey to the tune of endless likes and sponsorships, who wanted the dislikes at either end of a trucker’s daily fare?

Nonetheless with the theory drawing to a close in February of 2022, there was only the online tests to pursue at the authorised test centre. Bizarrely the most difficult of this would be ‘hazard detection’ and the only way to smash it was to have watched any number of practise videos of what they called ‘developing hazards’. Ironically it was entirely possible to fail this by having spotted these too early in their development and in truth the test was as much about technique as it was about spotting hazards, in the way that playing Poker successfully has a lot more to it than the cards in hand. Playing ‘Call of Duty’ repeatedly on your son’s Playstation was also an ideal form of preparation, as spotting a Soviet tank in a woodland environment soon enough was much like spotting the ethnically-neutral couple about to wheel the child’s buggy from behind a parked car.

All of that done, however, it was off to the practical lessons and this too harked back to those days when we’d drawn the air-stairs down from a dew-soaked Boeing at dawn of day. Except this would be in Ancoats, where I booked into a discount hotel as a precaution in order to be good to go on the first day of training. This might start as early as six o’clock, not least to avoid the traffic on the way out of Manchester itself. For the opening session though we would be starting off in a Class 2 or unarticulated truck of upto eighteen tonnes, for the cognoscenti out there. This felt overwhelming enough, as it must to be sat on say a 747 flight-deck having only seen the outside from within a 737. The reason for this was simple: most manufacturers use an identical cab whether the vehicle is articulated or not, so there were still three or four steps to negotiate by way of ingress. Although these are generally concealed by the door, some trucks have as many as five and these were well worth flaunting by taking that bit longer to close up. All such cabs in Europe, incidentally, are known as ‘over-cabs’ because they do not have that long snout that trucks in the US do. The reason for this is that the overall length of tractor unit and trailer in Europe is more constricting than in North America, to cater for any number of ancient towns here with decidedly narrow streets or overhanging storeys.

It was then decidedly pleasant to be driving around the lower reaches of Pennine hills on a Sunday morning and pulling up at stops where as often as not the instructor would get the steak sandwiches and mugs of coffee in. Perhaps unsurprisingly many of my instructors were ex-Army, one in particular having done tours of both Iraq and of Afghanistan and been involved in fire-fights in which few would survive. I took extra care not to upset these types for fear of say, insufficient sugar in the teas causing a PTSD-fuelled meltdown on the A6 short of Bolton.

The test itself took place in Atherton, a place we’d go for practise prior on an almost daily basis and which must, as one instructor pointed out, have been a shock to all those who’d bought houses along its leafy highways and byways. The one thing you’d have to say about driving trucks is that, as with airliners, once you got used to them you would find yourself going faster and faster if only for the fun of it. And when tired, quite easily forgetting that you were in something that bit longer than a car. Much like in an airliner too, it meant that whatever you might collide with would come off rather worse if indeed it were noticed at all by the driver. No truck has dual controls, and so there’d be the odd “Whoooaaah!” from instructors if say a right-turn at a T-junction commenced too soon would have taken say the traffic-light with it.

I did though pass each driving-test at first attempt, like a shooting star burning itself out before its time. Having done so at the ‘reversing into a parking spot’ was ever so pleasing, requiring much the same skill as playing hoopla with a bag over your head. And in fact everything the government had been saying proved to be right: there was a shortage of lorry-drivers in the UK, even if not necessarily the type I were. In order to get a job I eschewed looking at a laptop and instead just called up numbers painted on the back of trailers. Which is how I would land my first role, driving chemicals or containers from factory to plant, or plant to port.

I sat at the helm of a Mercedes on Day One, a man at the open side-window telling me that this lever did this and this button did that, and then suggesting I follow the truck in front ~ a bit like ‘Red Leader’ from RAF days ~ as he careered along the East Lancs road and onto Manchester’s rush-hour orbital M60. It required the sort of derring-do that had been familiar to me from decades in cockpits of one sort or another. In fact at the very outset, during an interregnum between university and the let-down that was life itself, I had found myself actually hitch-hiking through Richmond Park, one of the London ‘royal parks’. A man had drawn up in a Volvo and turned out to have been at one time the sort of auxiliary pilot who’d transport aircraft of various types between one base and another (the only role women were in fact allowed in the UK during WW2).

How was it, I had asked him? Well he would pitch up late afternoon or in the early evening, the chances were, and without so much as a risk assessment or high-visibility tabard he’d be handed a Pilot Manual to brush up with over lavish dinner at the Officer’s Mess and a few beers in the bar afterward. Then he’d wander out to whatever transport/bomber/fighter it happened to be, and kicked some tyres and lit the fires. Spellbinding.

I turned to thank him at the gatehouse on Kingston Hill where the park gave on to the avenue where I was staying, with the family of one of the ‘names’ at Lloyds of London.

“Good luck in life.” he said. Dead now, maybe… but living on in hearts.

|

| Chemical Brother? |

Monday, January 16, 2023

SCALING UP Chapter Nine

IT'S A FLYING CAR, PET

Although the design of eVTOLs can clearly run to years instead of months, this is no need to be discouraged. The average family car now takes the better part of ten years to go from concept to sales, and there is no guarantee at whichever stage that any model might succeed, at least in so far as repaying its development cost goes. In aviation the stakes are altogether larger, and at the time of writing the world’s largest airliner could better be described as the world’s largest white elephant, especially now that most of them are white beside elephantine, few airlines wanting to advertise their want of perspicuity.

There is ever a yin and yang in the conception of means of transport which vacillates between the mass of people and the personal, and as flight comes to be electrified along with road transport in an ever-warming world the options are as wide as ever. It is ten years since the sinking of the cruise-liner Costa Concordia, and if ever we needed to revisit the symbolism of the Titanic during the opening years of the 20th century in the 21st, then this would have been it: both involving opulence on the grandest scale being swallowed under a night sky by unforgiving Nature whilst chaos and confusion reigned.

There is something ironic about a civilisation bent upon building the very largest forms of transport which calls to mind the desert collapse of the statue of Ozymandias; else of the same civilisation bent upon producing motor-vehicles in ever greater numbers that are set to destroy the sphere of operation they were designed to operate in? Whilst this is scheduled to change with electrification of all that we know, it is clear that electric substitutes for practically everything with which we are familiar do little to ameliorate the situation, generally supplementing what we consume already instead of substituting for it. In other words it is the Tragedy of the Commons extended over time instead of space, for whereas if land is a free-for-all it will be over-exploited, if you ask the current generation to forego pleasures and conveniences in order that subsequent generations might do so, you can probably imagine the response.

But as Herman Hesse said of the flowers that continue to bloom in wartime, we are unlikely to cease fiddling whilst Rome burns and thus any number of products wholly unrelated to addressing the elephant in the room are likely to continue to be developed; not least flying forms of taxi. They will however tick the relevant boxes that politicians focussed on the short-term need ticking in environmental terms, and will thus continue unabated. For there is also the Law of Unintended Consequences, which as we saw from measures in Jimmy Carter’s designed to limit fuel-consumption, resulted in larger and more fuel-hungry cars than ever. Likewise if you or I could produce a cheap-as-chips flying vehicle now adapted to personal mobility then you could guarantee that its uptake would likely damage rather than salve our relations with Planet Earth.

But like those wretches working at the foot of DIY mining-shafts slaving to produce the cobalt we so desperately need for our luxury Teslas, we all need to earn a living and so far as I am concerned it is as much the case that I’d rather my son need not work for anyone else than himself that drives this development in the longer term. For at the end of the day aircraft are a lot of fun, and they are in all events a good deal more economic in operation than all other forms of transport, pound for pound, when you take its speed into account as well. For instance I see what we are building now as being a reasonable substitute in various applications for either boats or all-terrain vehicles. A case in point albeit one involving a billionaire would be Richard Branson’s own domestic situation in having to flit between tropical islands separated by just a few miles (oh, the misery!). How much easier to do this by settling back in the chair of an electrical ‘flying carpet’ and being transported from patio to patio than that schlep down to the jetty and up at the other end, with all of that banging and splashing in between?

Or dropping down to applications among middle classes, how about a means of being elevated to the ski-slopes that avoids all the costly and inflexible infrastructure, whilst at the same time costing a fraction of the expenses involved in launching a helicopter? Or at a level any of us could appreciate, being rescued at the sea-side as a result of a form of half-way house between a rigid inflatable and a coastguard’s helicopter? Else being spirited between one vessel at sea and another? Or being elevated above literal minefields instead of negotiating them on foot? Or adding eyes in the sky to survey or video drones? Or pylon-races accessible to people without Red Bull sponsorship?

And on and on, the one thing being that the newest technologies tend to get used in ways unforeseen by anyone, and least of all their progenitors. The most infamous case of this was possibly Alexander Graham Bell’s belief that the telephone would likely be used by people wanting to listen in on distant orchestral performances, but only discounting IBM’s declaration that the world would likely not need more than about five computers.

I think there is a need too to scale things back in terms of sophistication, or lack thereof, in an increasingly uncertain world. Dyson’s own vacuum cleaners are marvels of engineering with the resources of Formula One racing teams behind them, facts that are amply reflected in their price. But do they really do that much better a job than the Goblin ‘tube’ that I inherited from the old dear next door in South London that was easier to use and did what I consider to have been an altogether passable job? Or do we really need LED light-bulbs that cost around ten times what we would have spent on an incandescent type ten years previously, or are we just taking an inadvertently expensive piss into the wind?

Grumpy old man aside, however, let us examine the design of my most successful prototype to date, and the prospects for its continued development. We have seen that I liked its four-pronged body from its inception, as being the easiest possible airframe to cobble together in the garage next door using only basic materials and manual power-tools. In fact if push came to shove you barely even need an electrical supply to produce it, excepting the fact that hand-drills are no longer available to buy in the UK so far as I can tell.

Although it was always an awkward shape to manhandle and transport for one thing, whilst for another it was decidedly asymmetric in a world of design symmetry. Nonetheless when it comes to servicing the four-sided construct that is the quadcopter there is little to best it in terms of addressing weight and balance issues along with the associated wiring. Its other principal disadvantage however would be in the difficulty of including a sufficient undercarriage within its scope, and if nothing else the necessity for doing so had been reinforced by our experience at Llanbedr. Ideally beside the widest possible track, the motors and propellers also need to be raised as far as is feasible out of harm’s way, harm being the ground in this instance. At the same time the pilot had also to be protected by physically distancing the propeller blades from arms and legs, and this was something that was also enabled by the addition of a square frame that surrounds the original outline of four cantilevers.

There were additional nice-to-haves, like the fact that the motors could be repositioned so as to reflect the ideal crux arrangement with a propeller directly in front of the pilot, one behind and one to either side. In fact this simplest arrangement appeared in the very earliest drones as the simplest possible execution, as to steer it involves a very logical application of power to one or other motor, viz. that at the rear to go forward, that at the front to go backward and those on either side to initiate sideways motion. In fact if you look at the Mission Planner software that accompanies the flight controller, this is the first and foremost configuration that could (and still can) be programmed.

The four points of the square that are formed by the new perimeter also mean however that propellers can be positioned either over or under the airframe, whereas where they occupied the corner they could only be mounted top-side in view of the skids being fixed at these points to the underside. Beside this they also form points at which anything else can be mounted, whether an independent platform for the operator or an identical drone ‘stacked’ upon the first. Modularity and flexibility have long been my own watchwords in design, allied to a means of fabrication that allowed for components to be re-purposed time and agin in order to keep the cost of successive iterations of each design to a minimum.

Not least, too, it does appear in the original patent specification beside some among the foregoing prototypes, so that the DNA of the design ‘coda’ has been preserved. I think it would be true to say that you could look at any of these successive designs and link them to the same origin in the way that say IKEA furniture or Volkswagen cars all retain distinctive features that make them instantly recognisable.

With it constructed therefore toward the end of last year (2021 at time of writing), there still remained how best to wire to for control and among the other binary choices that a designer of a personal air vehicle has to make beside standing or seated operation, is how it is best controlled… whether automatically by computerised means, or by simple weight-shift? In much the same way as previous, however, the same reasoning came into play. Weight-shift, by which everything from snowboards to parafoils can be steered beside powered types of aircraft like gyroplanes, had been used fairly extensively by any number of experimental mega-drones designed to transport people. Nonetheless they remained a curiosity, a spectacle like those trapeze-artists that you’d enjoy watching at the circus without ever really wanting a go yourself. At the same time the tide of history appeared to be favouring computer control itself, now that the bulk of an automobile was dependent upon computer chips (to the dis-benefit of the post-pandemic supply chain). Being seated anyway rather discounted any chance of using weight-shift, and I had already preferred that to flying whilst stood upright (as indeed I had for half a lifetime in the airline business). The idea of sitting back in a Recaro with finger-tip control not unlike that I had enjoyed in an Airbus of one type or another would have distinct appeal.

And thus the die was set. As a precaution I spoke at length to the proprietor of 3DXR, from whom we are sourcing a number of new parts (not least because the experts in the field recommended not using parts involved in crashes or downpours, of which my own parts were veterans). In the event though I persuaded myself to salvage at least four motors and four propellers left undamaged from Llanbedr, not least due to the cost. Serendipity features in every human endeavour, and my unwillingness to spend more equally dictated the build of a quadcopter this time around instead of an octocopter. Nonetheless the subsequent results I feel to have amply borne this gut-feeling out.

There would, alas, be one more hurdle in a sequence off hurdles attending every human endeavour too. I had long transported prototypes on the open trailer, not least because there was a certain PR value in my fellow road-users seeing a giant drone go past with what appeared, Borat-like, to be a child on board. In Aled’s absence from the project due withdrawal, I had selected Angus instead (real name not withheld) to wire and tune the vehicle on a consultancy basis, and arriving at his workshop with the kit in tow he would at once point out that the motors had ingested grit from a rain-sodden motorway while any number of electrical components had been soaked from the same source. And being CAA-registered, refused to fly equipment of such dubious provenance.

It would thus have to return on the familiar trek North, where fortunately the benefit of building a quadcopter from octocopter parts was an abundance of spares. How though I had been put in contact with Angus, an ex-Army captain since self-sponsored in the drone industry and generally involved in experimental trials when not film or survey ~ is serendipitous in itself. My cousin still labours in the airline industry locally, but prior to this was in architecture and had not infrequently rendered my designs in SketchUp. He mentioned in passing though a New Year’s Day TV programme in which celebrity David Walliams had been tasked with getting the eponymous Chitty Chitty Bang Bang ( the flying car and the film) flying again in replica form. He did this by using sizeable drone motors at its corners, and reviewing the credits I contacted the expert involved. He was however is more generally involved in RC helicopters at the highest level, and whilst not wanting to get involved with drones again, put me on to ‘a man who could’.

Whereas the proprietor of 3DXR had at length listed the pitfalls for the unwary that were involved in scaling up drones, not least adverse harmonics and a lack of rigidity, Angus himself felt that the latter might prove to be the prototype’s Achilles’ Heel. On a more hopeful note, Aled himself looking at the airframe suggested that bar a couple of minor issues he figured it would fly and at the same time was reassured by the fact we had returned to the fold in so far as its relative conventionality was concerned. Thus it was that during a decidedly clement weather window at the start of December in 2021, a month that had proven equally auspicious for the Wright Brothers, we awaited news from further south on the Somerset Levels as to how things were progressing on the front line.

And then, literally out of the blue, a YouTube video dropped into my inbox like manna from heaven. The prototype had out-performed all expectations, and has gone on to impress whomever has viewed it since as the basis of what might be a very credible flying machine, and among the easiest to assemble. In fact I had been invited during the summer to pitch inline to investors at a revolution.areo town-hall event where if nothing else, its speed of assembly had impressed as somewhat quicker than IKEA furniture.

And all of this below twenty-five kilos at birth. The picture here though says it all, and what appears to be the faintest of cloud formations in the sky is in fact the test-pilots grinning visage, reflecting his own astonishment that both he and it could possibly be flying so well. Meanwhile if you liked it too, you needn’t click LIKE anywhere either…

|

| Orville, right? |

Saturday, January 14, 2023

SCALING UP Chapter Eight

PAV-ING THE WAY

Managing a development project is key to success at least as much as, if not moreso than formulating a working design. In retrospect what had happened at Llanbedr was as much a failure in communication as all else, and a failure to capitalise upon progress by omitting to apply the same diligence to the aftermath as to the preparation. The airline business itself had learned that a review of crew performance was also an essential element of success if accidents like Kegworth ~ where doubts within the cabin as to which engine had failed had not for whatever reason been passed on ~ were to be avoided.

There was also something of a gap in perception, Aled feeling that only minor mods to the tuning were required for success, whereas for me whether something worked or not was a more binary affair. In fact at the same facility the UK’s foremost eVTOL effort had crashed altogether more spectacularly, though this was not something that its billionaire sponsor would be in any hurry to admit. Nonetheless there is something about failure that triggers primeval responses in human beings, evolved as we are from a time when such failures would lead to death by predation if not starvation. The opposite at a time of hunting and gathering would be a perception of the blessedness or else luck that led to bounty, and thus it is easy to see why the bulk of humanity is as eager to ride along on successful bandwagons as it is to ostracise the apparently less successful.

In fact most casual observers would not have noticed that Vertical Aerospace had like most other developers in a brand-new field radically altered the appearance of each of their successive prototypes, and certainly this would not bother VCs: for the simple reason that they are as blind as the rest of us when it comes to backing winners. It has been pointed out that most financial analyst performs no better in the longer term on the stock market than would a chimpanzee throwing darts. Thus it was that their own venture would garner more government funding, along with private and public investment (in the form of SPACs) than any other on here shores, whilst yet to fly a single prototype with any measure of success. What people are investing in however is the fact that someone benefiting richly from sky-high energy prices (from owning one of the largest of UK suppliers) was less likely to fail than the rest of us.

It was though clear that the market for vertical electrical flight was beginning to polarise between ‘personal air vehicles’ or PAVs at the lowest end of the market, and urban ‘flying taxis’ at the uppermost. These latter products were in truth the only ones that investors could visualise a need for, stuck as they were themselves so often in traffic in and around the places where they worked, like London on New York. What they would not know, in all likelihood, was that whilst the helicopter was the only vehicle to have even approached this dream of unbridled freedom of the skies (and is used extensively as a flying taxi for the rich in Sao Paulo), when it was introduced its inventors themselves saw no clear application for it. In fact one pioneering brand of helicopter first saw a paid application in its use as a giant hair-dryer aimed at keeping cherry orchards in California frost-free.

Personal flying machines ~ essentially single-seat types ~ have thus always had a chequered history. On a broader scale, single-seat motorised vehicles like the Honda Super Cub still represent the most ubiquitous form of transport, and the sale of electrical scooters (despite the best efforts of authorities to suppress them) remain decidedly healthy. On a literally higher level, the Red Bull aircraft featured in stunts and racing are invariably single-seaters, as are nascent electrical air-racing types. And so there have always been any number of single-seat aeroplanes out there, but few single-seat helicopters have thrived in nearly the same way.

This is surprising in view of the fact the one requires the hassle of airports and runways whilst the other can be wheeled out of the garage and put directly into use. This is most likely a result of two principal factors, in so far as helicopters are a devil to maintain, and something in which you are more likely to meet your death in (as its celebrity customers like Colin McRae or Kobe Bryant might attest). Thus electrified ‘multicopters’ might alter the status quo in so far as they make it altogether easier to own and operate something similar, and at a much reduced cost. In other words they promise a sort of tipping point that we have witnessed with products like smartphones and flat-screen TVs, which look for so many years like they will never happen and then before you know it everyone has got one except maybe you.

The problem multicopter developers have, though, is an embarrassment of riches in so far as knowing quite how to distribute inexpensive motor and propellers around an air vehicle in ways that are both practical and attractive at the same time is the nub of the problem. With helicopters you effectively had no choice except the optimal, with a main rotor up top ideally adjacent its complex and expensive power-train, along with tail-rotor out back. It is something like the evolution of mammals that would supplant that of dinosaurs, in so far as a relatively limited range of very large and simple cold-blooded beasts would be replaced in time by a proliferation of smaller warm-blooded species in an inexhaustible supply of forms (a process taken further again by the yet smaller and yet more numerous insect classification).

At the same time as taking a punt then on what might most appeal to the average flyer, from our point of view we had still to meet the constraints of GoFly’s competition, that remained a focal-point for development. Whilst these eliminated a full-sized phone-box as a means of transporting an individual, there remained problems with the prototype most recently flight-tested, not least how to get in an out of it without the benefit of a step-ladder. You could always drop one of he sides of the box from the equation or else reduce its extent, although the moment you do so it loses structural integrity and has then to be made more substantial and therefore heavier. It may come to pass that a reasonable way of combining the platform we have now with a standing operator would be by use of the sort of three-sided structure known universally as a Zimmer-frame, and indeed DragonAir in Florida have long used such an arrangement with obvious success.

In the interim however the question would be whether to dismantle what we had, for better of for worse, and rebuild to another design or else stick with it. As I have hinted at, however, failure itself carries an odour that disinclines us as human beings and it is for this reason that thrown once from a saddle, many people prefer not to get back on. The great unknown to is whether you or I would want to remain standing in flight, as on an airborne cherry-picker, or sit back on say a Recaro seat. At time of writing the current prototype (which is set for the foreseeable for want of the energy to start all over again, if nothing else) is committed to the latter, and I feel that there are eminently good reasons for this.

Not least the fact that standing is a young person’s game. They like surfing, soccer, snowboarding and hanging around takeaways doing whatever they do nowadays instead of smoking. Whereas I prefer our flying machine to be a universal omnibus, who seating on both decks as it were. In fact the whole aim of the challenge in California had been the design of an aircraft for ‘Everyman’ or woman and we felt that the only prize that had been won on the day in the form of Pratt and Whitney’s Disruptor Prize was won by a prototype that far from being disruptive to the industry had been replaced shortly afterwards by its developers; plus the fact that you’d to mount it like a sexually-excited giant tortoise in a way that alienated practically every possible user except for hardened Ninjas. But then they were from Japan, I guess.

If you were going to be up there for any length of time, and as the technology improves that will be increasingly the case, then you wanted a measure of comfort. From a safety point of view too, a vertical impact such as that stemming from a heavy landing is least well met by standing upright. Tests in elevators have shown that the human frame can withstand a force of sixty times that of gravity and still survive intact if lying down, whereas impact in an upright position is a vertebrae-crusher at even modest speeds. If nothing else then you’ve learned by reading this book to lie down if ever you’re in a lift that goes into free-fall.

The principal problem from the design point of view is that requires more extensive protection from propeller blades for the lower limbs, although we have circumvented the problem in the finalised platform by re-locating them almost entirely beneath the flight-deck which will ~ in time ~ feature a protective grille. Nonetheless I made that decision ads to whether to start afresh by re-examining a number of designs that incorporated a seat int the sort of airframe that we had pioneered. In this event too the upper quad could be relocated where I had wanted it all along, in an overhead position.

The reason that these never got much beyond the model or mock-up stage, despite involving many weeks or months of consideration, was that the problem remained essentially the location of the flight-control computer. These are processors little larger than an OXO cube, and in fact are generally called as such: a cube that is, rather than an OXO. Nonetheless there is almost invariably just one of them, that has to be located in a central position. And as we have seen too, that becomes problematic whenever power is distributed over two levels separated vertically by a flight compartment.

The solution to this, I felt strongly, would be to isolate the two drones (upper and lower) so that they operated independently and yet in concert. This is eminently do-able as evidenced by the spectacular light-shows staged in China, were individual drones are manoeuvred in close proximity but with the sort of co-ordination only previously achieved by murmurations of starlings. Nonetheless it would up the costs to some extent, requiring as it did two separate controllers (although this would amount to only an extra £250, which was a drop in the ocean so far as our development budget was concerned).

Where the true cost lay, as ever, was in the re-wiring and tuning involved at Aled’s workshop facility, where frankly they had better things to do such as earning a living. At the same time, Aled himself was sceptical that this solution might work, as it strayed from industry practise and could not be guaranteed. In all fairness too he had just backed two horses at the expense of considerable time and effort, the most recent of which had fallen at the first hurdle and whose rider subsequently put it out of its misery without a by-your-leave.

As a means to address these fears I proffered a sort of half-way house arrangement in which I would wire the bottom end so as to produce nothing else but straightforward lift, whilst they programmed the top-end to do the steering. In many ways this jibed with the way a helicopter works anyway, in so far as its control is divided between ‘collective’ lift that simply drives you upwards, and ‘cyclic’ which takes you in the desired direction. There would be nor failsafe redundancy though as it applied to the prototype, although as this was set for a flight of a duration just long enough to secure some video footage, it hardly mattered. In terms of how this ‘collective’ lift might be arranged by myself by using the lower quad alone, nothing could be simpler from the point of view that any RC transmitter and receiver can be linked to electrical speed controllers in order to simply accelerate or decelerate them.

Even this however would not be sufficient to twist Aled’s arm, and whilst he remained an interested shareholder and may yet emerge from the eVTOL closet (and acknowledge that one way or another we shall all soon by flying in electrical aircraft) another phase of development had been entered for good or for ill. Accordingly I sent him a limited edition print of an Avro Vulcan and wished he and his team well. Thus it was that what you see at the head of this page appears only in Registered Design form, and likely to remain so.

If nothing else though in casting around for some place that improved on the garage in which to photograph it ~ registered designs requiring a plain background ~ I discovered Vessel Studios locally on Liverpool’s Dock Road. They have the benefit of an infinity wall, against which the prototype could be pictured, beside an unfailing variety of clients that you get to meet on the day. In fact studio time is such a rare commodity in London that any number of people travelled here to use the facility. On one such occasion, therefore, I followed a video production involving an interview with members of the cast of a forthcoming series of Doctor Who. And despite owning the most advanced form of time-travel in the Universe, they still ran late…

|

| Have phone-box, will travel. |

.jpg)