Again unduly tardy as ever but the findings from the above.

First off, though the IAG group comprises Aer Lingus/British Airways/Iberia I shan’t be codesharing with them in future (and the compensation claim is underway). I worked LHR for six years and when I discovered the DUB connection was based DUB and had to arrive LHR to collect, my heart sank. LHR runs at 100% capacity and therefore a breath of wind or touch of fog and every single flight is delayed (due spacing on approach).

Thus we got the usual airline bullshit ~ they’ll hold the flight for you ~ and eventually spent five hours in DUB awaiting a flight to JFK instead, from where there was 90 minutes prior to a night-flight to SFO. Arriving there at 01:30 Sunday instead of 15:30 Saturday we arrived at an accommodation un-staffed and went to Denny’s for breakfast instead at 02:00 a.m.

Just prior to booking a motel at extra cost, we tried one last time at NASA Ames and whilst Pete (Day) was illegally parked there for two minutes we were picked up by security, who eventually led us to a note that had been left regards accommodation keys. Happily (or unhappily for her) we were able to knock the (sleeping) night-shift worker for a set of keys and finally got to bed at around 04:00 a.m.

But this was California, and next day it was pancakes and maple syrup in the sunshine (and I was ‘en famille’ as kids don’t ever forget this shit).

Subsequently it was up and arranging the accommodation. Forty-three years ago I was inducted into aviation at RAF Finningley (and Pete rather earlier at another RAF base), and so we were used to the routine, specifically trying to figure out where the accommodation block was in the absence of any signage whatsoever.

That done I think it was as early as the following day Monday we drove out to Half Moon Bay airfield to scope the place out, reserved as it was for practise flying. Meantimes we dropped mother and son in San Fran for the sightseeing: 25 degrees each day and nary a cloud in the sky. This was warmer than they usually experience in February and in truth a little chill in shorts when you were out of the sun… but then it was snowing widely in the UK.

Not long into the trip though we rendezvous’d with Pete Bitar late one night, he having driven his ‘Verticycle’ on a trailer from Indiana the previous four days. Unfortunately his FAA-licensed drone pilot dropped out last minute (despite having the date in his diary two years prior), which made flying that bit harder for Pete and practically impossible for ourselves.

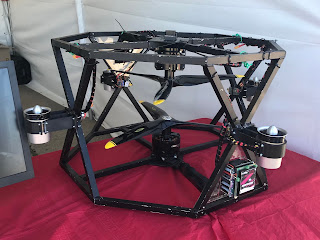

This was in view of the fact the drone had been stripped of four of its rotors and entered as a quad, under the weight that qualified it as a drone in the USA (but still requiring a qualified pilot). In retrospect as the vehicle had to survive four lots of airport baggage handlers, this was no bad thing, but it was combined with the fact that even given all eight motors the performance looked marginal when it came to lifting an adult (me).

Ironically what we had would almost certainly have raised my eight year-old son, and I was at pains to point out to the FAA that we could ship them as 55-pound vehicles, but that no-one could guarantee what would be put in them afterward that made them fly overweight… not least kids.

Wednesday was the briefing first thing for teams, and the move into the facilities the apron. In the event we did not set up either on this day, nor on the following (Thursday) which we spent at Half Moon Bay awaiting a back-up pilot who in the event failed to turn up. It meant that during that afternoon we’d to travel thirty-five miles north of the airfield beyond the Golden Gate and buy a receiver that matched this pilot’s transmitter (he being right-handed whilst the TELEDRONE was set up with a left-handed sidestick).

Sadly this meant that we had no presence at the airfield at NASA Ames during VIP day, when potential investors, the DOD and press were doing their interviews. I recall we went to the Winchester House instead… great movie if you get the chance.

Friday we were back out to Half Moon to collect the bottom half of the TELEDRONE as the back-up pilot announced (understandably) that driving out to Half Moon Bay to test the vehicle would take three hours of an already busy schedule. Arriving at Ames without ‘boots on the ground’ or batteries was proving an uphill struggle.

The remainder of the day was thus spent doing nothing much but waiting whilst the back-up pilot went through his own routine with the Pratt and Whitney judges, something that they should have been doing with us to had we managed to get the airframe airborne. Eventually come mid-afternoon we spent a good deal of time driving around looking for a place rather nearer where to test-fly the device. The pilot, a graduate of MIT with several hundred hours flying drones under his belt, wanted to review the battery-life and check the parameters from the laptop prior to launch, but unfortunately we hadn’t the code to hand to unlock it and besides, everyone in the UK was fast asleep in bed.

Accordingly you can see how we failed to replicate the flight indoors in the UK here…

… where there was a reasonable breeze blowing as you can hear. The considered opinion of the pilot ~ who admitted his piloting might could not be guaranteed given the lack of practise prior ~ was that in the absence of a GPS feed (which Alex had recommended) the change in latitude and longitude since the previous flight might have led to erroneous input from the compass facility that in turn resulted in not so much what he would call ‘fishtailing’ as the sort of instability he’d seen before that was much like a ball running around the surface of a bowl (toilet-bowl his actual suggestion).

With no spare props (another recommendation from Alex) that was about it, but frankly time had already run out for qualifying for the final line-up for the press and public Saturday.

Accordingly we’d no certificate for completing Phase Three as we had for Phase Two, and no press call on the day out on the apron in front of the crowd. We did however get a good reception from the public in the tent and made some reasonable contacts, and as we’d been among the last half-dozen slated to fly from among 854 teams I consider we hadn’t done to badly, although there’s no escaping he fact that we failed in the objective.

In retrospect however the fault has to be laid at my own door, although we did best we could in adapting to the circumstances. Looking back the organisers set the bar way to high, not least I feel because they were not technically adept at their own admission. In fact had we not suggested early on that there should be a ‘showcase’ category for those who couldn’t meet the half-hour’s flying criterion, I doubt there’d be anyone there at all.

Only one team out of the 854 in the form of Dragon Air got flying at all beside a wobbly hover (Team JAYU got a 1/4 scale model flying nicely, but then we could all have brought a radio-controlled model aeroplane), and even they crashed on the practise day due an ESC failure (and that was the lady’s fourth… which is why she rarely ventures above ten feet and even then over water).

All in all, for somebody with 15000 plus flying hours and who’d once entertained launching Bristow helicopters into Force 9 gales, I thought these things were fairly shit. On the other hand as the Pratt IP guy pointed out, all of the entrants to the original DARPA self-driving challenge were fairly shit too.

There’s no denying then that as with so much in California, the people there were all of a type willing to leave the day-job and sacrifice to the family to some extent in pursuit of an ideal, and I agree with Elon Musk that the USA is the only place to get done what is necessary to build the modern world. The UK is to my mind an old-money economy, where the prizes principally go to rentiers and bankers and nobody dare venture beyond the routine. If they set out trying to build something in a garage to get them airborne, they sooner or later sacrifice it on the altar of necessity.

But I blame myself entirely. My instinct given the configuration was to have gone for a quad with the larger U15 motors, which would have been easier to build and transport and rather better suited to lifting myself as an onboard pilot. This in turn would have meant I could have flown it myself under the Part 103 (Utility aircraft) category, which is altogether easier to pursue.

However it was the ‘engine-out’ capability that the organisers envisaged for the (not-to-happen) pylon race that forced us down the multi-copter route, and combined with fairly ludicrous limits on the dimensions. Dragon Air met the constraints, but only at the cost of a considerable load of batteries and eight of these U15s, whereas we would have made do with four (the weight of their vehicle some five times what ours was).

I was also deranged to expect anyone else beside myself and Pete (both involuntary retirees) to travel to California at the expense of the ‘day-job’. But then you live and learn.

All that said, there were plaudits from the FAA inspectors for the simplicity of the design (which again benefitted from four propellers in place of eight), and the press and public reception was altogether positive. There will be documentaries apparently from the likes of PBS, but these will appear between 12 and 18 months hence and so it is undoubtably worth continuing to develop a presence in the market in order to benefit.

Longer term too it does look like eight motors (minimum) will be ‘de rigeur’ for piloted operations, and so we are set fair and I’ve a re-configuration that should provide the extra thrust required.

I do not agree with Alex that a half-million pound budget is required to fly people in electrical VTOLs, but what I do know is that what people do does condition their responses, the way that for a hammer everything can be viewed as a nail. The Wright Brothers did not have the ‘reserves of power’ that people tell me that we need for this… in fact they had a deficit of power that was only answered by a 28-knot headwind on the day.

Nor do I think that the key is the regulation process. Electric scooters are unregulated and everyone using them is acting illegally. So there’s no global market for electric scooters, right? Or the ATVs that people ride on roads? Or drones that transmit pictures (and to my knowledge it remains illegal to transmit video from an airborne source without a broadcast licence to do so in the UK). Fact is, if you wait for the regulators to catch up with the market then you’ll be dead sooner. Remember the red flag required for motor-cars in the UK? Well that lasted a few months, didn’t it?

Fact is, life’s not worth living without a project.

And in conclusion we couldn’t have got this far without Pete’s presence and funding, Tom’s review of the IP, Phil’s solderings and musings, Alex’s specification and testing, Martin’s fixing and flying.

Whether I continue is moot, but I’ve all the materials to continue and don’t see why I shouldn’t.

Colin H, March 11th 2020